The heat is on indeed. From its flashy, racy first scene to its sad, dramatic finale, “Miss Saigon” is a captivating melodrama that will take you through just about the entire range of human emotion.

It’s playing at the Segerstrom Center now through October 13.

Viewers under the age of 14 are discouraged from attending, and for good reason.

The musical takes a no-holds-barred look at the seedy underbelly of a war-torn region.

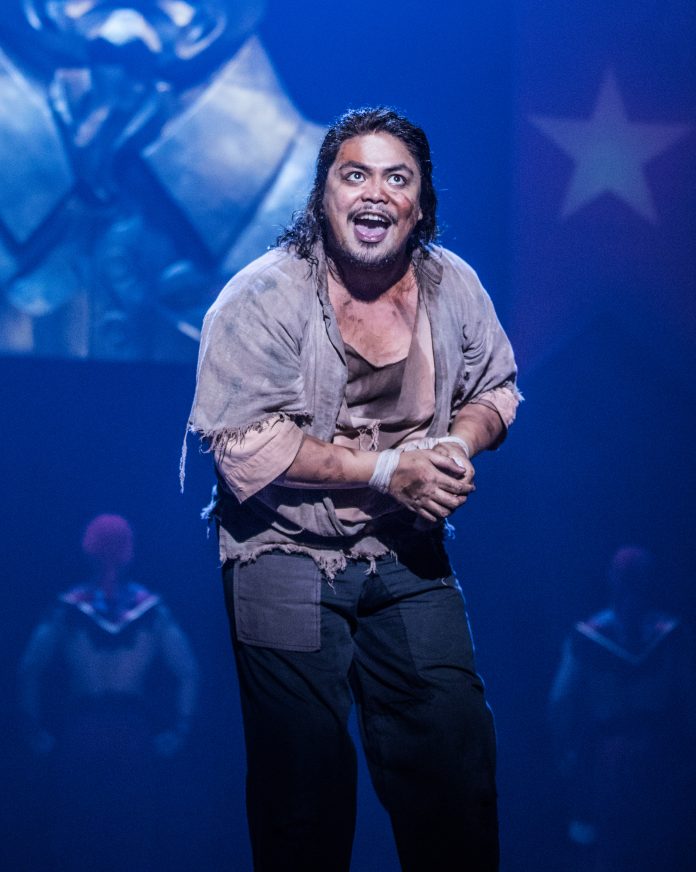

Both of the leads—Emily Bautista as Kim and Anthony Festa as Chris—as well as Red Concepcion as The Engineer, are excellent.

The set opens in “Dreamland”—a nightclub in 1970s Saigon, frequented by American GIs. And for all the filth the nightclub scenes depict, they are some of the most entertaining and eye-catching numbers of the entire show, with their flashy lights strung across the stage, and perfectly 1970s-looking ladies in their nightclub best.

Kim, a young woman who’s just arrived in the city after her family and hometown fell victim to the war, is given a job at Dreamland by The Engineer, the club’s owner.

She soon develops a connection with client and soldier Chris, who promises to marry her and take her out of the country.

Suddenly it’s three years later, 1978, there’s a new regime, Kim is impoverished and Chris is nowhere to be found, until we get a flash of him in his life in America with a wife.

There’s a sequence with Vietnamese soldiers and a dragon that shows us the might of the new regime. Dancers move in formation under the new regime’s flags and a giant bust of Ho Chi Minh in a number that is haunting but captivating. The Engineer is brought before the Commissar, who happens to be a man who long ago was pledged in marriage to Kim in an arranged marriage. The Engineer has been a prisoner in a camp, but the commissar requested to speak with him, as he is now looking for Kim again and thinks he will know where she is.

The Engineer tracks Kim down—she’s living in a shantytown. The commissar sees her, and under threat, wants to take her with him to be his wife. She refuses, as she still dreams of Chris, and hopes that he will come back for her. She then reveals a surprise—she has a son.

The commissar is ashamed of Kim and comes up with his solution—kill the boy, Tam, so no one has to worry about him or his origins, and he and Kim can start anew. Kim of course refuses this, things escalate, and she kills the commissar.

The curtain falls on the first act as the Army discovers what’s happened, and searches for Kim as she and Tam flee for their lives.

Act II opens in 1978 America, at a conference for the Bui Doi Organization, which raises awareness to help the children left behind—often literally abandoned and left to orphanages or the streets—fathered by American GIs and born to Vietnamese women left behind in the country.

John, a veteran and friend of Chris’, is behind the organization’s efforts and receives the news that Chris has a son. He tells Chris and Chris’ well-meaning wife, and they decide they must go find Kim and the boy and see what they can do to help.

Meanwhile, Kim, Tam and The Engineer have relocated to Bangkok, where they are once again in the nightclub business.

There Kim has a “nightmare” and we are finally shown a flashback that reveals what happened to separate her and Chris. Back in 1975, Saigon fell, the Americans were issued quick orders to be evacuated immediately, and despite Chris’ efforts to contact Kim, and vice versa, she and the rest of the Vietnamese clamoring with their paperwork outside the embassy gate were left behind.

This is where the famous helicopter scene happens. In this production’s iteration, a holographic helicopter is flashed on the stage, before the curtain parts and a real one hovers yards above the stage. It’s a crowd-pleaser, and between the noise and flashing lights, it effectively depicts the chaos.

Flash forward and Kim is told Chris is, at long last, coming to see her and she is understandably thrilled.

However he and his wife, Ellen, arrive, and when they all meet, Ellen is news to Kim and she is devastated to learn that she cannot be Chris’ wife, but begs them to at least take Tam with them to America.

They insist that he needs his mother and they ought not raise him as their own.

And in the musical’s finale, Kim takes her own life inside the nightclub, Chris mourns her tragic life and their lost love, and he and Ellen do take Tam with them.

And that is the show’s dramatic ending, with no flash-forwards or musical events to tie it all together or cheer the audience up. It is a deeply complex, mature and raw production in the best of ways; it lays it all out there for the audience, then abruptly leaves them to process and take from it what they will.

Its R-rating gives it the ability to go deep and be complex, which mostly works, but some of the language and sensuality are a bit gratuitous.

The cast all complements each other very well, and it’s so captivating and truly keeps you on the edge of your seat if you’re not familiar with the story—and perhaps will have the same effect even if you are.

The national tour of “Miss Saigon” makes for a heartbreaking, dramatic and entertaining outing to the theater, and is worth your time.

It plays at the Segerstrom Center through this Sunday, October 13.

See scfta.org.