With well over half a century spent providing musical inspiration to students K-12 in and around Orange County, Chuck Wackerman needs no introduction to Los Al Unified district residents.

His legendary musical education has, by now, touched thousands of lives by instilling in them a love for and strong work ethic around playing music.

That said, little is known about the experiences that inspired and shaped this educational pillar of the community who is a skilled musician in his own right.

Though anybody who knows the Wackerman family knows several of the Wackerman men including Chuck are highly skilled drummers, few know that Chuck’s first instrument was the trumpet.

‘Mr. Wackerman’ as he is known still by his students, regardless of how old they get, was one of two sons born to a piano-playing mother and a non-musician but avid music fan father in Pittsburgh, PA in 1930.

At the age of nine, Chuck and family moved to Alhambra, CA and a year later, he began learning how to play trumpet.

By the time he was set to graduate from Alhambra High, the young Wackerman had had the privilege of taking private lessons from a cornetist who had played with the king of the marching band arrangement John Philip Sousa, recording artist Charles “Del” Staigers.

Chuck met Del Staigers toward the end of Staigers’ life, so their time together was brief, yet invaluable.

“In about six months [with Staigers] I learned much more than I did from the other [my first] teacher in three years,” Wackerman said.

He began teaching himself drums freshman year of high school but continued playing trumpet in concert band mostly, joining the marching band for one year during high school as well.

A standout horn player, one of his teachers suggested he try out for union membership, which Chuck did, successfully, at the age of eighteen.

After high school, he took courses at Pasadena City College and Westlake College and worked at the Fitzsimmons market where his father was a buyer/supplier, before anticipation of being drafted into the Korean War found him, on the suggestion of his future brother-in-law, Brooks Coleman, enlisting with the Air National Guard.

Ironically, before the war, Chuck’s high school trumpet teacher had offered to get him into an Air Force band, which he declined. After all, the Nat’l Guard required less of a time commitment, but he was destined to become a trumpeter in the Air Force’s 562nd Band when the Air National Guard base he was stationed at was called to service.

“As soon as I joined, they activated the whole base,” Chuck said.

He spent approximately seventeen months in the military, mostly serving at George Air Force Base in Victorville, CA, and after the Korean War picked up his education first back at Pasadena City, then joining a few wartime friends at U.C. Santa Barbara and finally ended up at USC where he earned his bachelor and master’s degrees in music and education.

After being discharged, he decided that, as the big band era was ending, he would find a more stable career path ahead as a music teacher than solely as a gigging jazz musician.

It was only after his time in the service that Mr. Wackerman started taking drum lessons.

He studied under bebop drummer Roy Hart, West Coast jazz drummer Charles Flores and Academy Award-winning sound effects artist and drum legend Murray Spivack.

About Spivack, Wackerman said, “he had everything analyzed: the angle of your stick, and the height of the stick, the weight of the stick; he had everything figured out scientifically. The whole basis of his teaching was relaxing, so if you tense up, you’re doing it wrong.”

Also, around this time, Wackerman joined a quartet (on drums) led by guitar great Vic Garcia and joined by Garcia’s wife on vocals and tambourine and Larry Smethers on bass.

They recorded one album together at a studio on Sunset Blvd. under the name Vic Garcia & Germaine called “Up Up & Then Some.”

Almost immediately after graduating from USC, in 1957 Chuck was hired at McGaugh Elementary and has remained a resident and music teacher in the district ever since.

Eventually, he taught at Oak and McAuliffe Middle students, then at Los Alamitos High, and the Orange County (High) School of the Arts, until around 2019-20 when instruction moved to an online format that Chuck found unworkable.

When asked when he officially retired though, he wryly said, “Oh, I never retired.”

For about five years early in his teaching career, Chuck was a gigging lounge musician until the grueling schedule and four hours of sleep a weeknight began to take their toll, at which point he stopped playing except for summertime stints including in Las Vegas.

He has fond memories of playing with his quartet at Reuben E. Lee restaurant in Newport and Tustin, CA and at several venues in Vegas including lounges at Caesar’s Palace and the now-closed Thunderbird Hotel, though he regrets never finding the time to catch Frank Sinatra, who had a residency at the time.

Still, the Wackermans have witnessed and participated in performances by a laundry list of legends.

For example, about watching Frank Zappa rehearse with one of Chuck’s sons, Chuck said, “it took me about two seconds to realize this guy’s a genius. He was rehearsing the band, singing all the parts, and stopping them every second. It was very intense rehearsal.”

As for Barbra Streisand, Wackerman recalled his son “Chad played with her … You know, I’ve often heard that she can be very difficult, and Chad said, he told her, ‘You know I never do this but,’ he said, ‘I have to tell you you’re unbelievable’ … and she said, ‘you are too.’ She was super nice, so you can’t go by what people say about people.”

When it comes to enjoying official performances, one musician that sticks out in Chuck’s memory is Maynard Ferguson.

“He was a showman, the audience would just go crazy, he was like a rockstar,” said Wackerman.

It is around the time that he stopped gigging during the school year, circa 1961-62, that he brought jazz to McGaugh Elementary.

By some accounts, this was the first elementary school jazz program in California.

The very first festival competition McGaugh entered at Orange Coast College had no division for elementary school students, so they were lumped in with the junior high bands and still managed to win first place.

Chuck’s skills as an educator eventually led to a victory for the Los Al Big Band and OCHSA’s Jazz Combo at the most prestigious Reno Jazz competition and an individual Most Outstanding Musician award for the band’s drummer, the youngest (Brooks) Wackerman, in 1993.

About their victory stadium performance in Reno, Chuck said it was, “probably the most exciting performance that I ever had.”

Not only did the homegrown talent of his sons (who Chuck personally taught starting them as early as five years old) help keep his bands in lock step to place in festival after festival, Mr. Wackerman also decided already by McGaugh’s second festival appearance to commission some original music.

The first was from John Prince, who composed a piece called “Big Bad Chad” named for one of Wackerman’s sons.

This gave a stellar band with an outstanding teacher an even bigger advantage at competitions.

“Nobody had the music,” Chuck says of those early days.

“I was the only one that had it. So many festivals we’d go to, and they were playing stock arrangements; you’d have five or six bands all playing the same music, so I didn’t want to do that. I wanted things that were more original.”

In 1971, Wackerman innovated again by kicking off the renowned Class Notes concert series, an annual fundraising event showcasing LAUSD’s jazz bands and featuring guest performers (playing with their own bands and with Chuck’s students) from the roster of pros, including Louis Belson, Bill Watrous and Tom Kubis, that Chuck had come to know, some through the musician’s union he joined as a high school senior.

Justin Padilla, current LAHS jazz program director, who has carried this tradition forward under the name Spotlight concert series said “Chuck had the experience of twenty teachers [combined] … and the heart of a saint. One of his superpowers was the ability to make a band of middle school musicians perform as clean as a professional band. With a master like that … there are only two things you can do; try to copy his approach and avoid attending the same festivals he took his band to,” he said

“He had the support of the community and the respect of the world,” said Padilla.

Chuck has won several awards and honors for his achievements in music education including from the Orange County Board of Education in 2012.

“I miss it … Interacting with the students and seeing kids improve and become really good musicians and … even one’s that don’t stick with it … they derive something out of it, enjoyment, and they learn to appreciate music better.”

Former student and professional musician K.J. Ticehurst remembers, “He was so passionate about the school jazz programs and it resonated in the way he conducted us. I was lucky enough to work with Mr. Wackerman throughout my middle and high school years.”

Wackerman’s legacy is alive and well, carried forward by all those he has taught and played music with and through his kids and grandkids.

His late wife, Barbara, was also a pillar of the community and according to Chuck supported him “in a million ways over the years.”

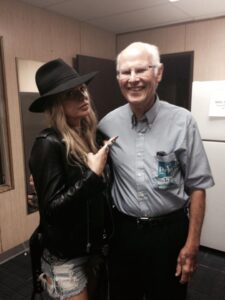

From his relationship with countless amazing musicians and motivating generations of students, to seeing a son open for rock legends Metallica, whose current bassist is a family friend, and a granddaughter make it to the finals on “American Idol” season eighteen, Chuck Wackerman’s place in music history and legacy of work in service of the arts and his community is undeniable.